Behind the scenes

Jane Fitts

“No ideas but in things.”

For graphic designer Jane Fitts, this is not a philosophy. It’s a job. It is Fitts’ job to craft facsimiles of reality for film and television sets. For historical movies, she fabricates a fictional reality. For a futuristic film, she fabricates a realistic fiction. These spaces must be both invisible and believable at the same time. We don’t notice them, but they influence us.

For more than 20 years, since studying graphic design at Art Center College of Design, Fitts has been fabricating objects and artifacts that, like the actors, are protagonists — ideas and stories as much as objects. She has made signage, maps, champagne bottles and product packaging for directors that include Michael Mann, Spike Jonze and David Fincher. She’s worked on The Morning Show, Big Little Lies and American Horror Story. She’s created album covers, fly posters and airplane liveries for Magic City. City seals, IDs and badges for characters in 24 were not allowed to replicate the real thing, but they had to look just as convincing.

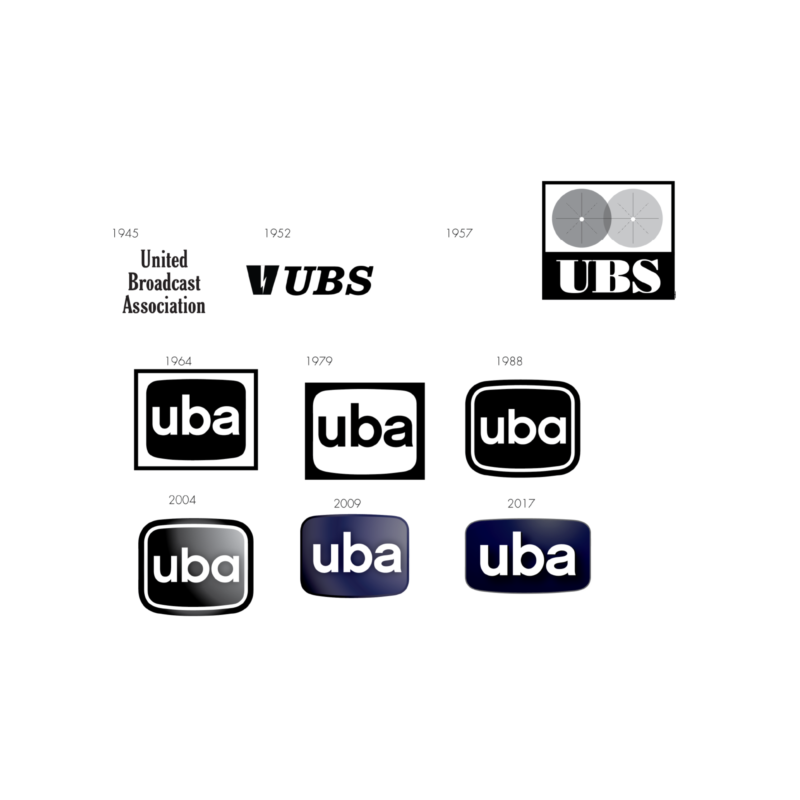

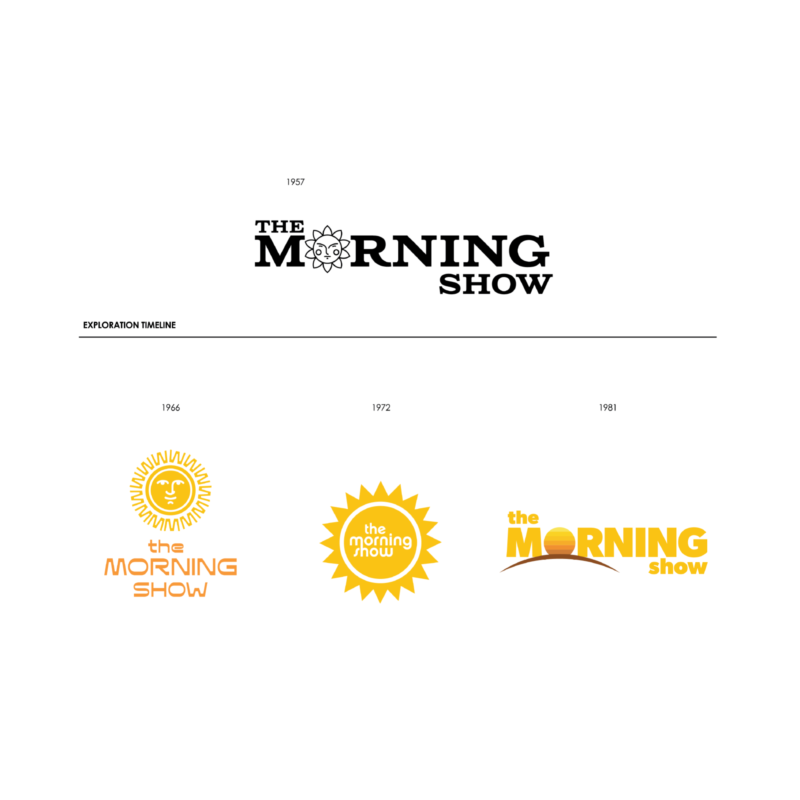

The Morning Show: Chronological brand design of network logo and Morning Show logo, for display in lobby of news network.

Not only does she need to know what she’s making, but why. How it will be used, what it means, may determine how she makes it. Fitts was asked to make a turn-of-the-19th-century map for the film Master & Commander as a background prop or set dressing, so she ink-jet printed a base layer on period-appropriate paper and then hand-painted map features over that. If she had been asked instead to make the map a “hero” prop, which becomes the focus of a character in a macro-shot on camera, she would have hand-letterpressed the bottom layer before painting it, or inked it, with old fountain pens and nibs, entirely by hand. Not understanding or being aware of this distinction, someone involved in production allowed it to be used as an insert shot, resulting in a goof call-out on the film database site, IMDB.

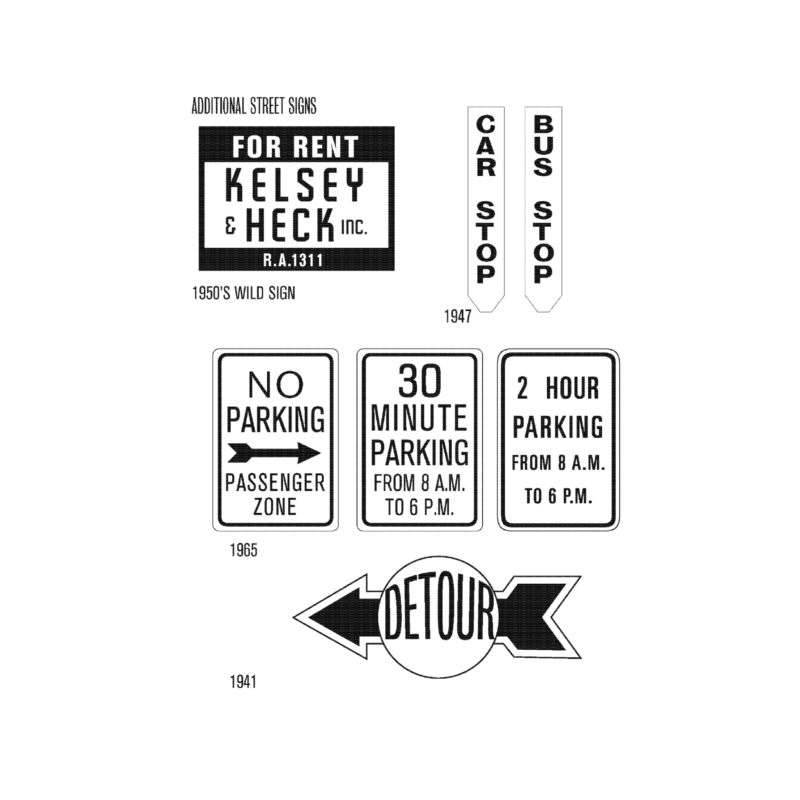

Consultants can be good resources: a policeman, a rabbi, a school teacher. “I search them out,” she admits, “because I can’t be an expert in everything. I have to lean in and use the village.” But much of the time she’s doing her own research and, in a sense, working around the clock. She has tapped friends in law enforcement and the law, for example, to tour a DEA office, a SWAT office and the Pentagon. She takes snapshots of diplomas in her doctor’s office, nurses’ badges at the hospital and her daughters’ kindergarten classrooms. “It’s about being aware of all the stuff around us. Any time I’m anywhere, I’m taking photographs,” she says. Before shooting starts in LA for a show set in Baltimore, she boots up Google Earth. “What do street signs look like in Baltimore? Are they blue or green? Am I going to offset my sign or kern it off on purpose? What material were signs made on in 1925?” she asks. “How do I speak the language of Baltimore?”

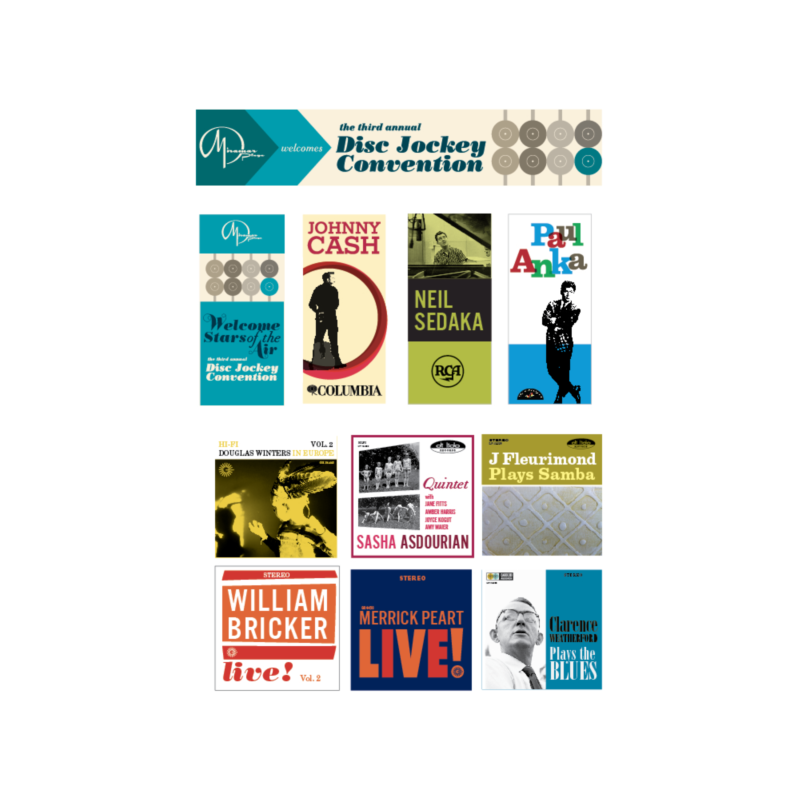

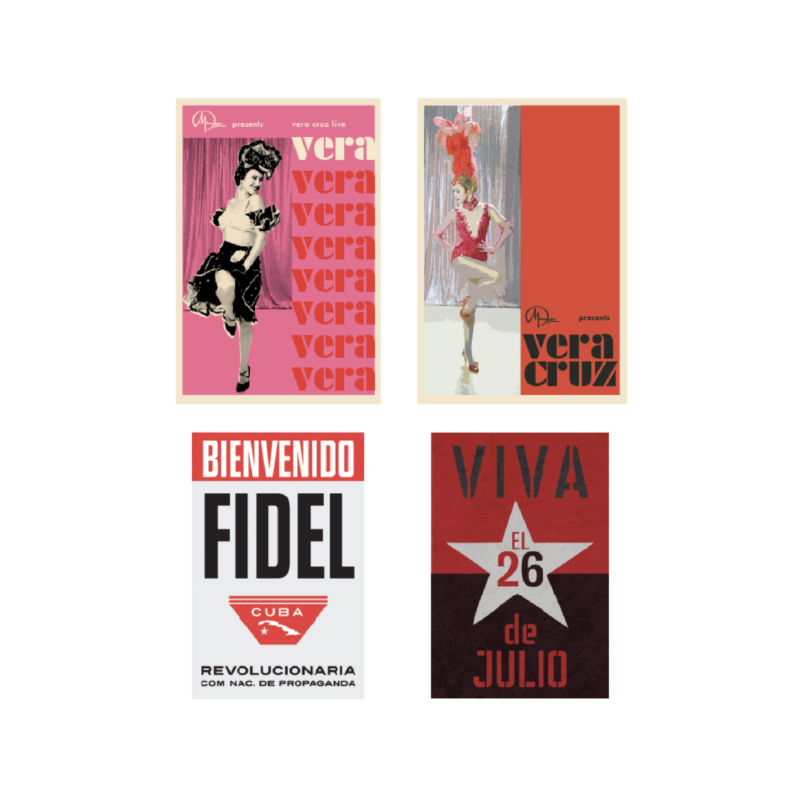

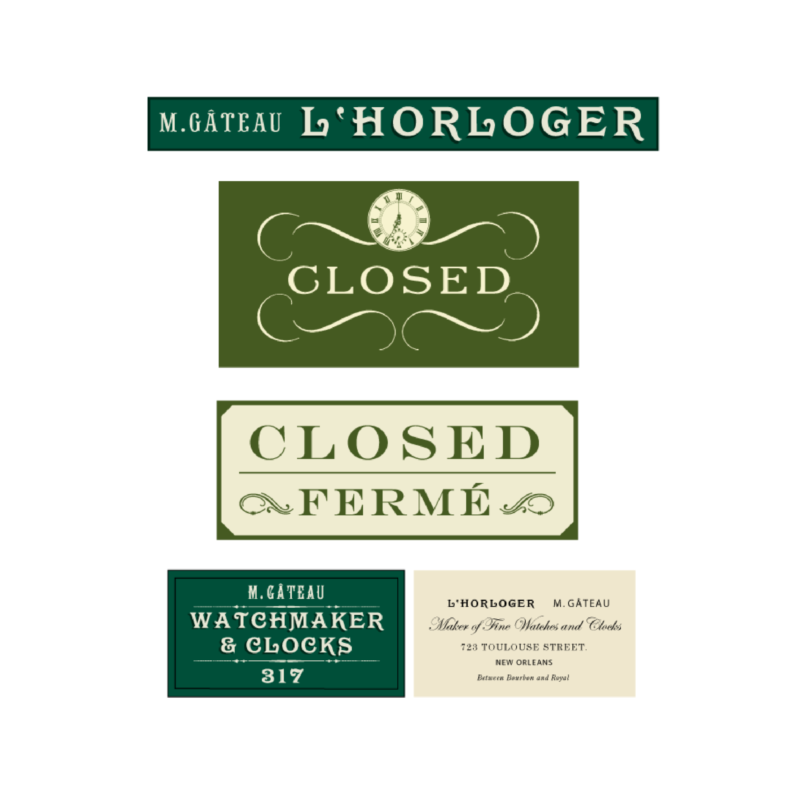

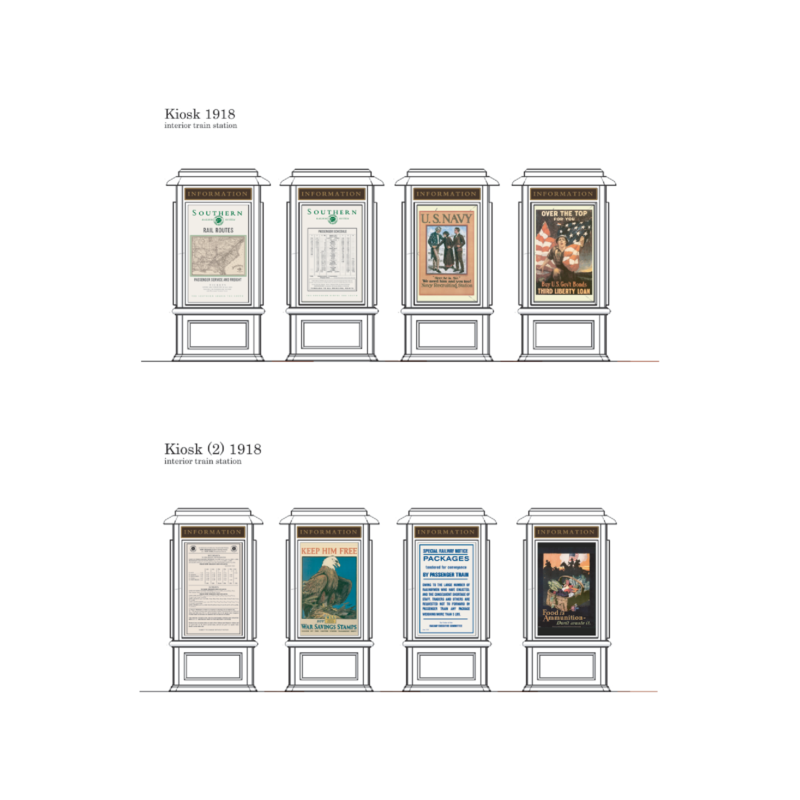

Magic City: 1960s period graphics, airline branding, various music and show posters, Fidel propaganda.

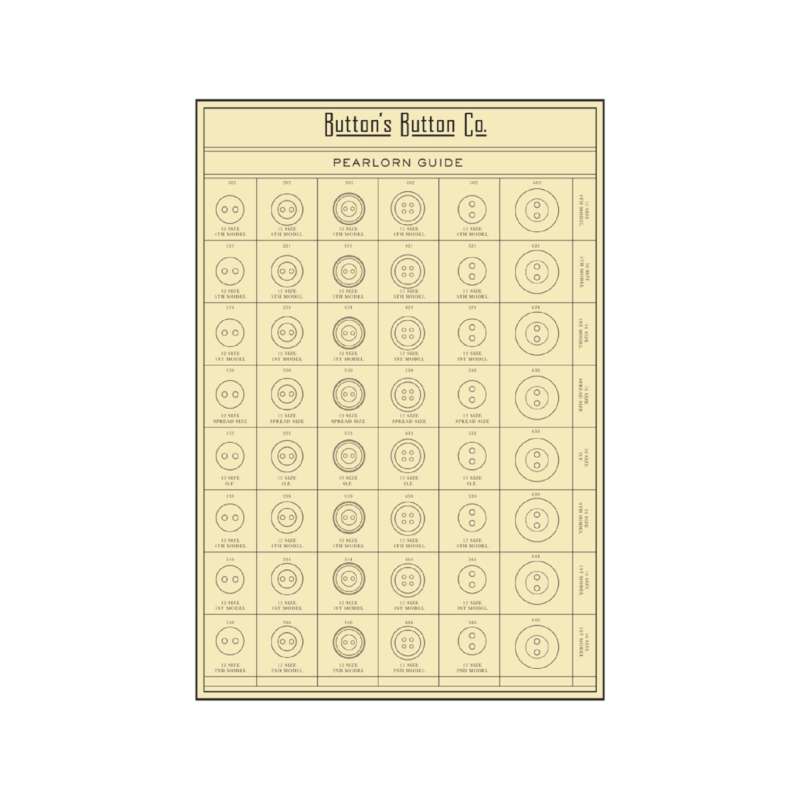

For years, Fitts has been building a library of brimming binders, a flat file filled with items like water-stained price tags or yellowing newspapers bought at flea markets, estate sales or antiquarian shows, and a digital database of photos, size currently unknown. These are important tools that allow her to work at the pace required by the industry: five to seven days of prep for a TV episode and three to four months for feature films.

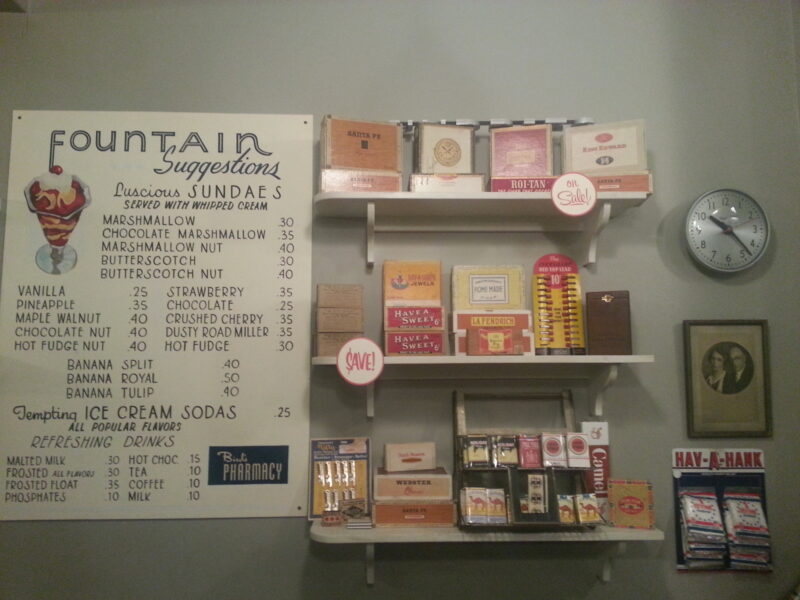

American Horror Story, Freak Show: Period packaging design and signage for pharmacy.

Technology “allows me to stay at my desk,” she says. Google image searches catalog objects across hundreds of years. Travels via Google Earth give a sense of locations. But, to check facts and get a sense of scale and texture, she still does gumshoe investigation, going to places like the Smithsonian or The Huntington Library. Technology also, for better and worse, allows anyone to access almost any information, making accuracy more important than ever for those who don’t want to star on an IMDB goof call-out. It also quickens the pace of production. “I can send the artwork digitally without leaving my desk,” she says, “but the people who have to make these objects physically have to make them faster.”

As does she, and her library helps. Fitts generated binders and binders of research for The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, about a man who aged backward, requiring the creation of ephemera across multiple eras. “But I never cull it down,” she says of her library. “Everything comes back again.”

The databases help in another way: “It’s really hard to make the crappy stuff, to do the ‘bad’ work, so I want to reference it, to make it authentic. When I see something really ‘bad’, I take a photo. I have photos of rusty old signs and I can tell the person making a replica: ‘Age the sign down like this.’” At other times, she has to create “shabby”-looking background vehicles in order to hide things on the street that the camera shouldn’t see: plumbing vans, delivery vehicles, graffitied box trucks and so on.

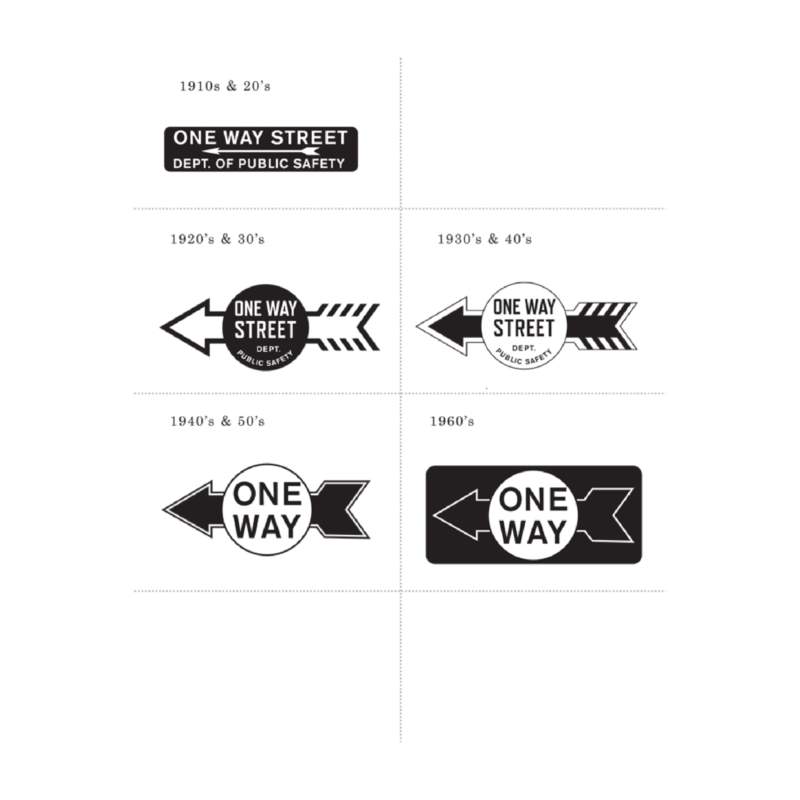

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button: Various period signage and packaging, showing progression over time.

Fitts tends to work from a typography-oriented graphic design perspective. She did a month of research on typography, period signage and graphic design for Benjamin Button, making a huge spreadsheet noting, for example, when each typeface was created and when it was most popular. “The typeface is your character. Who’s going to speak the language of the film? Is it going to be Bodoni? Kepler? What does a newspaper look like? Because I studied art history, I gather a lot of information, but the typeface is the lead actor. It’s a personal thing for me. It’s very important to get that right.”

More: Fancygraphics.net

Story: Shonquis Moreno

Featured Surfaces